34 posts tagged “sandboxing”

2026

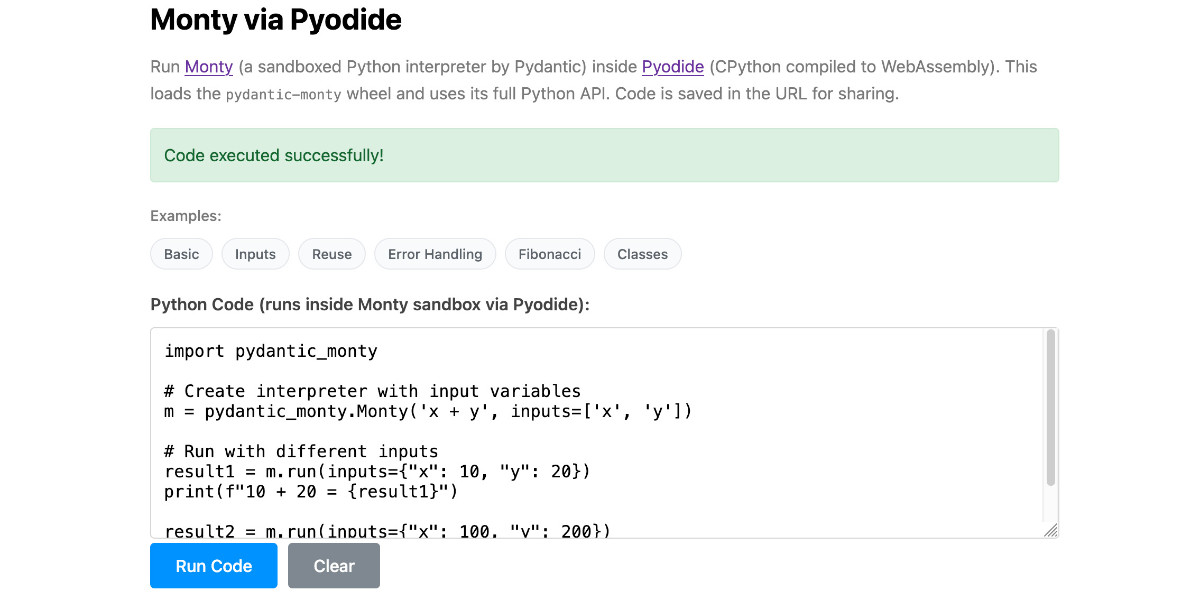

Running Pydantic’s Monty Rust sandboxed Python subset in WebAssembly

There’s a jargon-filled headline for you! Everyone’s building sandboxes for running untrusted code right now, and Pydantic’s latest attempt, Monty, provides a custom Python-like language (a subset of Python) in Rust and makes it available as both a Rust library and a Python package. I got it working in WebAssembly, providing a sandbox-in-a-sandbox.

[... 854 words]Introducing Deno Sandbox (via) Here's a new hosted sandbox product from the Deno team. It's actually unrelated to Deno itself - this is part of their Deno Deploy SaaS platform. As such, you don't even need to use JavaScript to access it - you can create and execute code in a hosted sandbox using their deno-sandbox Python library like this:

export DENO_DEPLOY_TOKEN="... API token ..."

uv run --with deno-sandbox pythonThen:

from deno_sandbox import DenoDeploy sdk = DenoDeploy() with sdk.sandbox.create() as sb: # Run a shell command process = sb.spawn( "echo", args=["Hello from the sandbox!"] ) process.wait() # Write and read files sb.fs.write_text_file( "/tmp/example.txt", "Hello, World!" ) print(sb.fs.read_text_file( "/tmp/example.txt" ))

There’s a JavaScript client library as well. The underlying API isn’t documented yet but appears to use WebSockets.

There’s a lot to like about this system. Sandboxe instances can have up to 4GB of RAM, get 2 vCPUs, 10GB of ephemeral storage, can mount persistent volumes and can use snapshots to boot pre-configured custom images quickly. Sessions can last up to 30 minutes and are billed by CPU time, GB-h of memory and volume storage usage.

When you create a sandbox you can configure network domains it’s allowed to access.

My favorite feature is the way it handles API secrets.

with sdk.sandboxes.create( allowNet=["api.openai.com"], secrets={ "OPENAI_API_KEY": { "hosts": ["api.openai.com"], "value": os.environ.get("OPENAI_API_KEY"), } }, ) as sandbox: # ... $OPENAI_API_KEY is available

Within the container that $OPENAI_API_KEY value is set to something like this:

DENO_SECRET_PLACEHOLDER_b14043a2f578cba...

Outbound API calls to api.openai.com run through a proxy which is aware of those placeholders and replaces them with the original secret.

In this way the secret itself is not available to code within the sandbox, which limits the ability for malicious code (e.g. from a prompt injection) to exfiltrate those secrets.

From a comment on Hacker News I learned that Fly have a project called tokenizer that implements the same pattern. Adding this to my list of tricks to use with sandoxed environments!

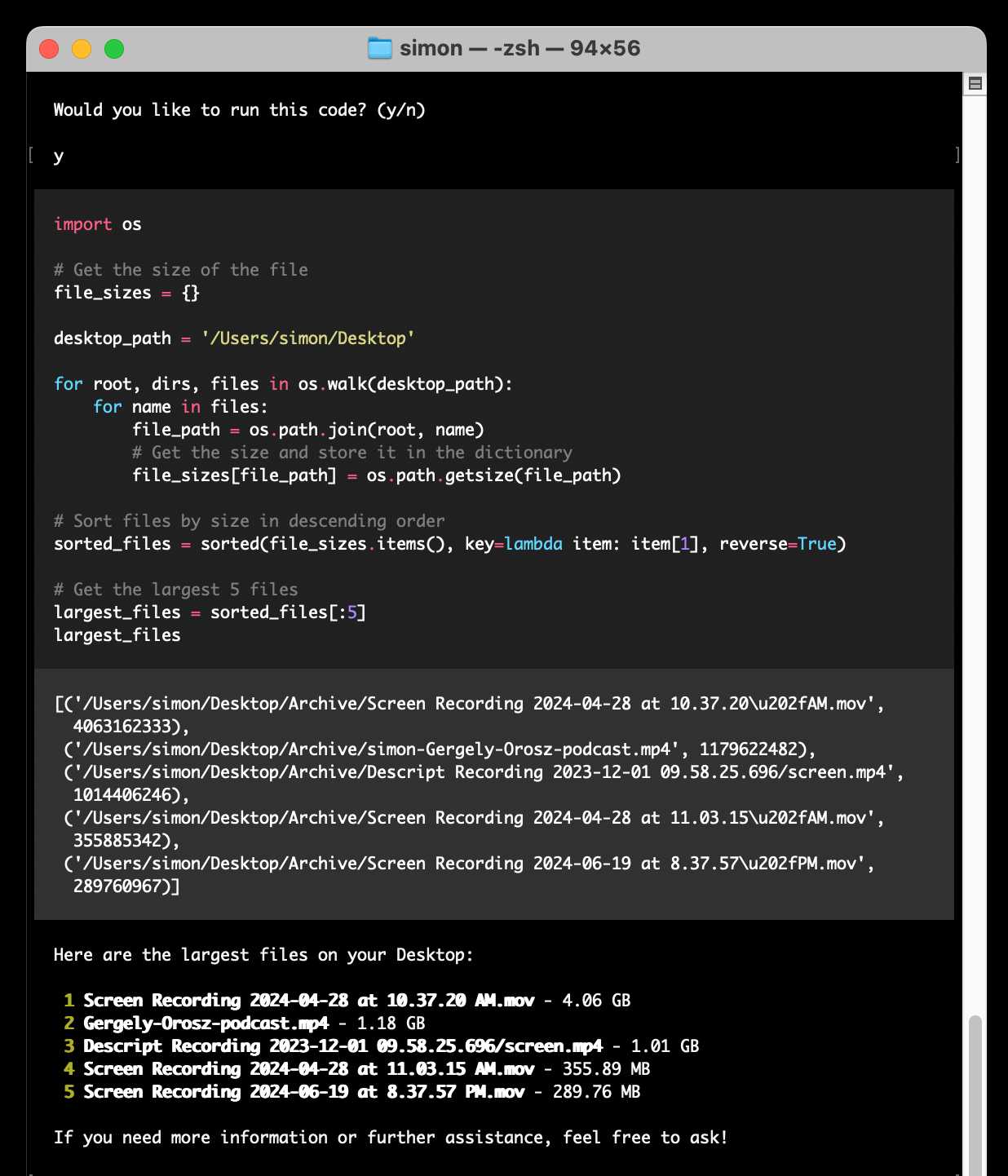

Introducing the Codex app. OpenAI just released a new macOS app for their Codex coding agent. I've had a few days of preview access - it's a solid app that provides a nice UI over the capabilities of the Codex CLI agent and adds some interesting new features, most notably first-class support for Skills, and Automations for running scheduled tasks.

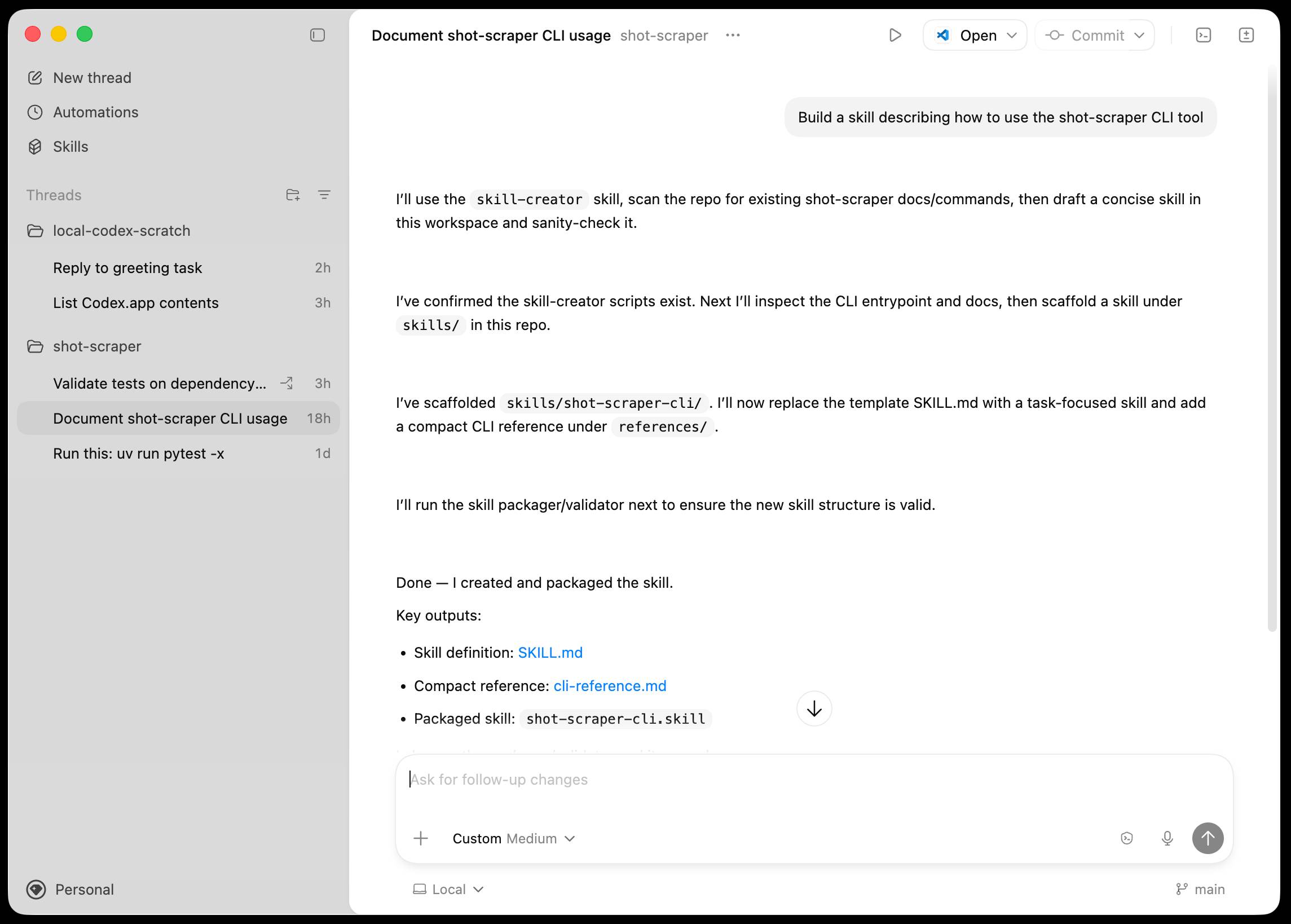

The app is built with Electron and Node.js. Automations track their state in a SQLite database - here's what that looks like if you explore it with uvx datasette ~/.codex/sqlite/codex-dev.db:

Here’s an interactive copy of that database in Datasette Lite.

The announcement gives us a hint at some usage numbers for Codex overall - the holiday spike is notable:

Since the launch of GPT‑5.2-Codex in mid-December, overall Codex usage has doubled, and in the past month, more than a million developers have used Codex.

Automations are currently restricted in that they can only run when your laptop is powered on. OpenAI promise that cloud-based automations are coming soon, which will resolve this limitation.

They chose Electron so they could target other operating systems in the future, with Windows “coming very soon”. OpenAI’s Alexander Embiricos noted on the Hacker News thread that:

it's taking us some time to get really solid sandboxing working on Windows, where there are fewer OS-level primitives for it.

Like Claude Code, Codex is really a general agent harness disguised as a tool for programmers. OpenAI acknowledge that here:

Codex is built on a simple premise: everything is controlled by code. The better an agent is at reasoning about and producing code, the more capable it becomes across all forms of technical and knowledge work. [...] We’ve focused on making Codex the best coding agent, which has also laid the foundation for it to become a strong agent for a broad range of knowledge work tasks that extend beyond writing code.

Claude Code had to rebrand to Cowork to better cover the general knowledge work case. OpenAI can probably get away with keeping the Codex name for both.

OpenAI have made Codex available to free and Go plans for "a limited time" (update: Sam Altman says two months) during which they are also doubling the rate limits for paying users.

ChatGPT Containers can now run bash, pip/npm install packages, and download files

One of my favourite features of ChatGPT is its ability to write and execute code in a container. This feature launched as ChatGPT Code Interpreter nearly three years ago, was half-heartedly rebranded to “Advanced Data Analysis” at some point and is generally really difficult to find detailed documentation about. Case in point: it appears to have had a massive upgrade at some point in the past few months, and I can’t find documentation about the new capabilities anywhere!

[... 3,019 words]the browser is the sandbox. Paul Kinlan is a web platform developer advocate at Google and recently turned his attention to coding agents. He quickly identified the importance of a robust sandbox for agents to operate in and put together these detailed notes on how the web browser can help:

This got me thinking about the browser. Over the last 30 years, we have built a sandbox specifically designed to run incredibly hostile, untrusted code from anywhere on the web, the instant a user taps a URL. [...]

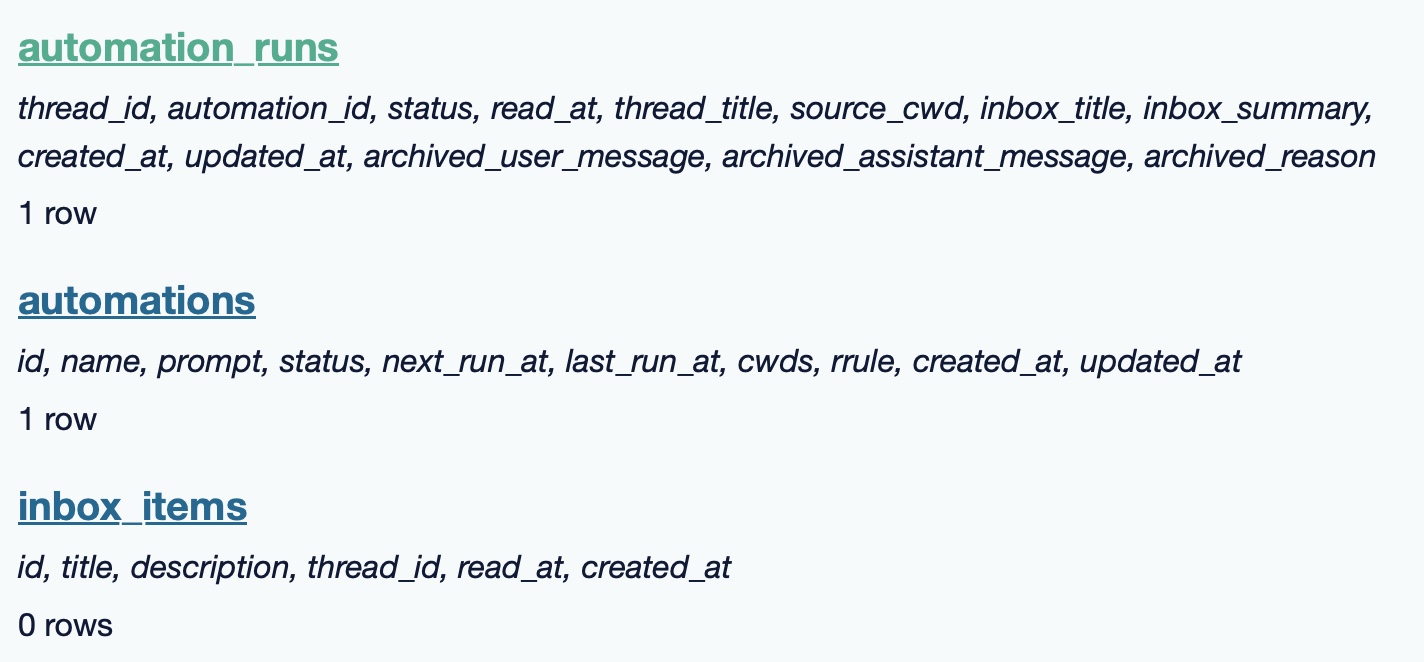

Could you build something like Cowork in the browser? Maybe. To find out, I built a demo called Co-do that tests this hypothesis. In this post I want to discuss the research I've done to see how far we can get, and determine if the browser's ability to run untrusted code is useful (and good enough) for enabling software to do more for us directly on our computer.

Paul then describes how the three key aspects of a sandbox - filesystem, network access and safe code execution - can be handled by browser technologies: the File System Access API (still Chrome-only as far as I can tell), CSP headers with <iframe sandbox> and WebAssembly in Web Workers.

Co-do is a very interesting demo that illustrates all of these ideas in a single application:

You select a folder full of files and configure an LLM provider and set an API key, Co-do then uses CSP-approved API calls to interact with that provider and provides a chat interface with tools for interacting with those files. It does indeed feel similar to Claude Cowork but without running a multi-GB local container to provide the sandbox.

My biggest complaint about <iframe sandbox> remains how thinly documented it is, especially across different browsers. Paul's post has all sorts of useful details on that which I've not encountered elsewhere, including a complex double-iframe technique to help apply network rules to the inner of the two frames.

Thanks to this post I also learned about the <input type="file" webkitdirectory> tag which turns out to work on Firefox, Safari and Chrome and allows a browser read-only access to a full directory of files at once. I had Claude knock up a webkitdirectory demo to try it out and I'll certainly be using it for projects in the future.

The Design & Implementation of Sprites (via) I wrote about Sprites last week. Here's Thomas Ptacek from Fly with the insider details on how they work under the hood.

I like this framing of them as "disposable computers":

Sprites are ball-point disposable computers. Whatever mark you mean to make, we’ve rigged it so you’re never more than a second or two away from having a Sprite to do it with.

I've noticed that new Fly Machines can take a while (up to around a minute) to provision. Sprites solve that by keeping warm pools of unused machines in multiple regions, which is enabled by them all using the same container:

Now, today, under the hood, Sprites are still Fly Machines. But they all run from a standard container. Every physical worker knows exactly what container the next Sprite is going to start with, so it’s easy for us to keep pools of “empty” Sprites standing by. The result: a Sprite create doesn’t have any heavy lifting to do; it’s basically just doing the stuff we do when we start a Fly Machine.

The most interesting detail is how the persistence layer works. Sprites only charge you for data you have written that differs from the base image and provide ~300ms checkpointing and restores - it turns out that's power by a custom filesystem on top of S3-compatible storage coordinated by Litestream-replicated local SQLite metadata:

We still exploit NVMe, but not as the root of storage. Instead, it’s a read-through cache for a blob on object storage. S3-compatible object stores are the most trustworthy storage technology we have. I can feel my blood pressure dropping just typing the words “Sprites are backed by object storage.” [...]

The Sprite storage stack is organized around the JuiceFS model (in fact, we currently use a very hacked-up JuiceFS, with a rewritten SQLite metadata backend). It works by splitting storage into data (“chunks”) and metadata (a map of where the “chunks” are). Data chunks live on object stores; metadata lives in fast local storage. In our case, that metadata store is kept durable with Litestream. Nothing depends on local storage.

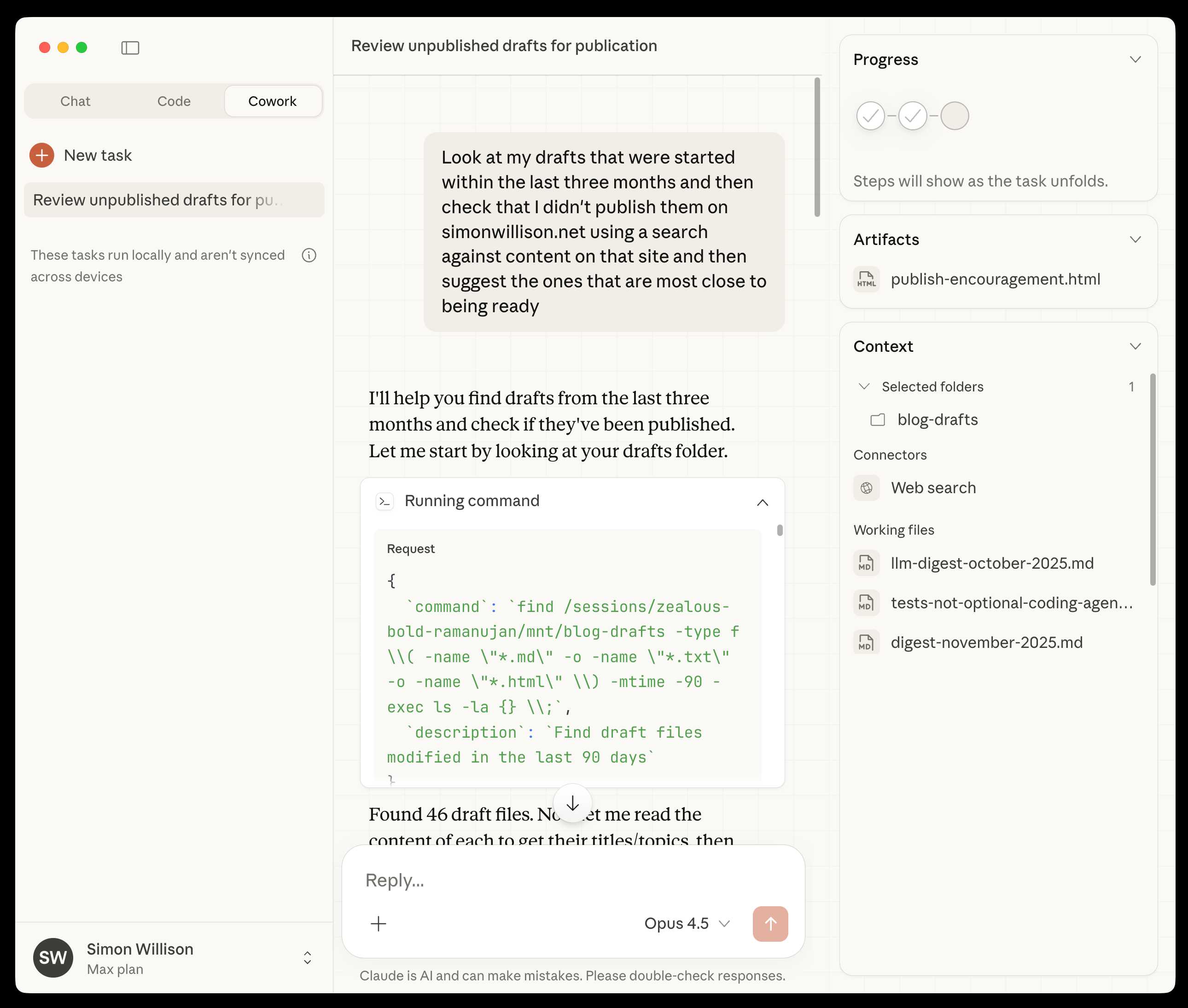

First impressions of Claude Cowork, Anthropic’s general agent

New from Anthropic today is Claude Cowork, a “research preview” that they describe as “Claude Code for the rest of your work”. It’s currently available only to Max subscribers ($100 or $200 per month plans) as part of the updated Claude Desktop macOS application. Update 16th January 2026: it’s now also available to $20/month Claude Pro subscribers.

[... 1,863 words]Fly’s new Sprites.dev addresses both developer sandboxes and API sandboxes at the same time

New from Fly.io today: Sprites.dev. Here’s their blog post and YouTube demo. It’s an interesting new product that’s quite difficult to explain—Fly call it “Stateful sandbox environments with checkpoint & restore” but I see it as hitting two of my current favorite problems: a safe development environment for running coding agents and an API for running untrusted code in a secure sandbox.

[... 1,560 words]LLM predictions for 2026, shared with Oxide and Friends

I joined a recording of the Oxide and Friends podcast on Tuesday to talk about 1, 3 and 6 year predictions for the tech industry. This is my second appearance on their annual predictions episode, you can see my predictions from January 2025 here. Here’s the page for this year’s episode, with options to listen in all of your favorite podcast apps or directly on YouTube.

[... 1,741 words]A field guide to sandboxes for AI (via) This guide to the current sandboxing landscape by Luis Cardoso is comprehensive, dense and absolutely fantastic.

He starts by differentiating between containers (which share the host kernel), microVMs (their own guest kernel behind hardwae virtualization), gVisor userspace kernels and WebAssembly/isolates that constrain everything within a runtime.

The piece then dives deep into terminology, approaches and the landscape of existing tools.

I think using the right sandboxes to safely run untrusted code is one of the most important problems to solve in 2026. This guide is an invaluable starting point.

2025

MicroQuickJS. New project from programming legend Fabrice Bellard, of ffmpeg and QEMU and QuickJS and so much more fame:

MicroQuickJS (aka. MQuickJS) is a Javascript engine targetted at embedded systems. It compiles and runs Javascript programs with as low as 10 kB of RAM. The whole engine requires about 100 kB of ROM (ARM Thumb-2 code) including the C library. The speed is comparable to QuickJS.

It supports a subset of full JavaScript, though it looks like a rich and full-featured subset to me.

One of my ongoing interests is sandboxing: mechanisms for executing untrusted code - from end users or generated by LLMs - in an environment that restricts memory usage and applies a strict time limit and restricts file or network access. Could MicroQuickJS be useful in that context?

I fired up Claude Code for web (on my iPhone) and kicked off an asynchronous research project to see explore that question:

My full prompt is here. It started like this:

Clone https://github.com/bellard/mquickjs to /tmp

Investigate this code as the basis for a safe sandboxing environment for running untrusted code such that it cannot exhaust memory or CPU or access files or the network

First try building python bindings for this using FFI - write a script that builds these by checking out the code to /tmp and building against that, to avoid copying the C code in this repo permanently. Write and execute tests with pytest to exercise it as a sandbox

Then build a "real" Python extension not using FFI and experiment with that

Then try compiling the C to WebAssembly and exercising it via both node.js and Deno, with a similar suite of tests [...]

I later added to the interactive session:

Does it have a regex engine that might allow a resource exhaustion attack from an expensive regex?

(The answer was no - the regex engine calls the interrupt handler even during pathological expression backtracking, meaning that any configured time limit should still hold.)

Here's the full transcript and the final report.

Some key observations:

- MicroQuickJS is very well suited to the sandbox problem. It has robust near and time limits baked in, it doesn't expose any dangerous primitive like filesystem of network access and even has a regular expression engine that protects against exhaustion attacks (provided you configure a time limit).

- Claude span up and tested a Python library that calls a MicroQuickJS shared library (involving a little bit of extra C), a compiled a Python binding and a library that uses the original MicroQuickJS CLI tool. All of those approaches work well.

- Compiling to WebAssembly was a little harder. It got a version working in Node.js and Deno and Pyodide, but the Python libraries wasmer and wasmtime proved harder, apparently because "mquickjs uses setjmp/longjmp for error handling". It managed to get to a working wasmtime version with a gross hack.

I'm really excited about this. MicroQuickJS is tiny, full featured, looks robust and comes from excellent pedigree. I think this makes for a very solid new entrant in the quest for a robust sandbox.

Update: I had Claude Code build tools.simonwillison.net/microquickjs, an interactive web playground for trying out the WebAssembly build of MicroQuickJS, adapted from my previous QuickJS plaground. My QuickJS page loads 2.28 MB (675 KB transferred). The MicroQuickJS one loads 303 KB (120 KB transferred).

Here are the prompts I used for that.

Living dangerously with Claude

I gave a talk last night at Claude Code Anonymous in San Francisco, the unofficial meetup for coding agent enthusiasts. I decided to talk about a dichotomy I’ve been struggling with recently. On the one hand I’m getting enormous value from running coding agents with as few restrictions as possible. On the other hand I’m deeply concerned by the risks that accompany that freedom.

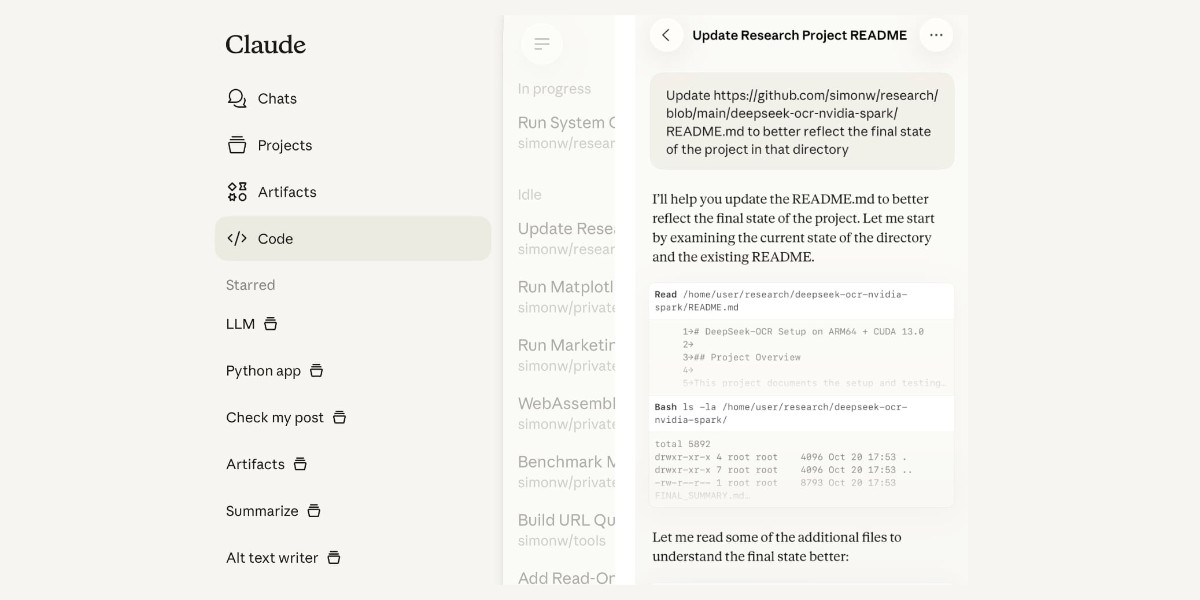

[... 2,208 words]Claude Code for web—a new asynchronous coding agent from Anthropic

Anthropic launched Claude Code for web this morning. It’s an asynchronous coding agent—their answer to OpenAI’s Codex Cloud and Google’s Jules, and has a very similar shape. I had preview access over the weekend and I’ve already seen some very promising results from it.

[... 1,434 words]httpjail

(via)

Here's a promising new (experimental) project in the sandboxing space from Ammar Bandukwala at Coder. httpjail provides a Rust CLI tool for running an individual process against a custom configured HTTP proxy.

The initial goal is to help run coding agents like Claude Code and Codex CLI with extra rules governing how they interact with outside services. From Ammar's blog post that introduces the new tool, Fine-grained HTTP filtering for Claude Code:

httpjailimplements an HTTP(S) interceptor alongside process-level network isolation. Under default configuration, all DNS (udp:53) is permitted and all other non-HTTP(S) traffic is blocked.

httpjailrules are either JavaScript expressions or custom programs. This approach makes them far more flexible than traditional rule-oriented firewalls and avoids the learning curve of a DSL.Block all HTTP requests other than the LLM API traffic itself:

$ httpjail --js "r.host === 'api.anthropic.com'" -- claude "build something great"

I tried it out using OpenAI's Codex CLI instead and found this recipe worked:

brew upgrade rust

cargo install httpjail # Drops it in `~/.cargo/bin`

httpjail --js "r.host === 'chatgpt.com'" -- codex

Within that Codex instance the model ran fine but any attempts to access other URLs (e.g. telling it "Use curl to fetch simonwillison.net)" failed at the proxy layer.

This is still at a really early stage but there's a lot I like about this project. Being able to use JavaScript to filter requests via the --js option is neat (it's using V8 under the hood), and there's also a --sh shellscript option which instead runs a shell program passing environment variables that can be used to determine if the request should be allowed.

At a basic level it works by running a proxy server and setting HTTP_PROXY and HTTPS_PROXY environment variables so well-behaving software knows how to route requests.

It can also add a bunch of other layers. On Linux it sets up nftables rules to explicitly deny additional network access. There's also a --docker-run option which can launch a Docker container with the specified image but first locks that container down to only have network access to the httpjail proxy server.

It can intercept, filter and log HTTPS requests too by generating its own certificate and making that available to the underlying process.

I'm always interested in new approaches to sandboxing, and fine-grained network access is a particularly tricky problem to solve. This looks like a very promising step in that direction - I'm looking forward to seeing how this project continues to evolve.

Something I've realized about LLM tool use is that it means that if you can reduce a problem to something that can be solved by an LLM in a sandbox using tools in a loop, you can brute force that problem.

The challenge then becomes identifying those problems and figuring out how to configure a sandbox for them, what tools to provide and how to define the success criteria for the model.

That still takes significant skill and experience, but it's at a higher level than chewing through that problem using trial and error by hand.

My x86 assembly experiment with Claude Code was the thing that made this click for me.

Two interesting new products for running code in a sandbox today.

Cloudflare launched their Containers product in open beta, and added a new Sandbox library for Cloudflare Workers that can run commands in a "secure, container-based environment":

import { getSandbox } from "@cloudflare/sandbox";

const sandbox = getSandbox(env.Sandbox, "my-sandbox");

const output = sandbox.exec("ls", ["-la"]);Vercel shipped a similar feature, introduced in Run untrusted code with Vercel Sandbox, which enables code that looks like this:

import { Sandbox } from "@vercel/sandbox";

const sandbox = await Sandbox.create();

await sandbox.writeFiles([

{ path: "script.js", stream: Buffer.from(result.text) },

]);

await sandbox.runCommand({

cmd: "node",

args: ["script.js"],

stdout: process.stdout,

stderr: process.stderr,

});In both cases a major intended use-case is safely executing code that has been created by an LLM.

WWDC: Apple supercharges its tools and technologies for developers. Here's the Apple press release for today's WWDC announcements. Two things that stood out to me:

Foundation Models Framework

With the Foundation Models framework, developers will be able to build on Apple Intelligence to bring users new experiences that are intelligent, available when they’re offline, and that protect their privacy, using AI inference that is free of cost. The framework has native support for Swift, so developers can easily access the Apple Intelligence model with as few as three lines of code.

Here's new documentation on Generating content and performing tasks with Foundation Models - the Swift code looks like this:

let session = LanguageModelSession( instructions: "Reply with step by step instructions" ) let prompt = "Rum old fashioned cocktail" let response = try await session.respond( to: prompt, options: GenerationOptions(temperature: 2.0) )

There's also a 23 minute Meet the Foundation Models framework video from the conference, which clarifies that this is a 3 billion parameter model with 2 bit quantization. The model is trained for both tool-calling and structured output, which they call "guided generation" and describe as taking advantage of constrained decoding.

I'm also very excited about this:

Containerization Framework

The Containerization framework enables developers to create, download, or run Linux container images directly on Mac. It’s built on an open-source framework optimized for Apple silicon and provides secure isolation between container images.

I continue to seek the ideal sandboxing solution for running untrusted code - both from other humans and written for me by LLMs - on my own machines. This looks like it could be a really great option for that going forward.

It looks like apple/container on GitHub is part of this new feature. From the technical overview:

On macOS, the typical way to run Linux containers is to launch a Linux virtual machine (VM) that hosts all of your containers.

containerruns containers differently. Using the open source Containerization package, it runs a lightweight VM for each container that you create. [...]Since

containerconsumes and produces standard OCI images, you can easily build with and run images produced by other container applications, and the images that you build will run everywhere.

Build AI agents with the Mistral Agents API. Big upgrade to Mistral's API this morning: they've announced a new "Agents API". Mistral have been using the term "agents" for a while now. Here's how they describe them:

AI agents are autonomous systems powered by large language models (LLMs) that, given high-level instructions, can plan, use tools, carry out steps of processing, and take actions to achieve specific goals.

What that actually means is a system prompt plus a bundle of tools running in a loop.

Their new API looks similar to OpenAI's Responses API (March 2025), in that it now manages conversation state server-side for you, allowing you to send new messages to a thread without having to maintain that local conversation history yourself and transfer it every time.

Mistral's announcement captures the essential features that all of the LLM vendors have started to converge on for these "agentic" systems:

- Code execution, using Mistral's new Code Interpreter mechanism. It's Python in a server-side sandbox - OpenAI have had this for years and Anthropic launched theirs last week.

- Image generation - Mistral are using Black Forest Lab FLUX1.1 [pro] Ultra.

- Web search - this is an interesting variant, Mistral offer two versions:

web_searchis classic search, butweb_search_premium"enables access to both a search engine and two news agencies: AFP and AP". Mistral don't mention which underlying search engine they use but Brave is the only search vendor listed in the subprocessors on their Trust Center so I'm assuming it's Brave Search. I wonder if that news agency integration is handled by Brave or Mistral themselves? - Document library is Mistral's version of hosted RAG over "user-uploaded documents". Their documentation doesn't mention if it's vector-based or FTS or which embedding model it uses, which is a disappointing omission.

- Model Context Protocol support: you can now include details of MCP servers in your API calls and Mistral will call them when it needs to. It's pretty amazing to see the same new feature roll out across OpenAI (May 21st), Anthropic (May 22nd) and now Mistral (May 27th) within eight days of each other!

They also implement "agent handoffs":

Once agents are created, define which agents can hand off tasks to others. For example, a finance agent might delegate tasks to a web search agent or a calculator agent based on the conversation's needs.

Handoffs enable a seamless chain of actions. A single request can trigger tasks across multiple agents, each handling specific parts of the request.

This pattern always sounds impressive on paper but I'm yet to be convinced that it's worth using frequently. OpenAI have a similar mechanism in their OpenAI Agents SDK.

MCP Run Python (via) Pydantic AI's MCP server for running LLM-generated Python code in a sandbox. They ended up using a trick I explored two years ago: using a Deno process to run Pyodide in a WebAssembly sandbox.

Here's a bit of a wild trick: since Deno loads code on-demand from JSR, and uv run can install Python dependencies on demand via the --with option... here's a one-liner you can paste into a macOS shell (provided you have Deno and uv installed already) which will run the example from their README - calculating the number of days between two dates in the most complex way imaginable:

ANTHROPIC_API_KEY="sk-ant-..." \ uv run --with pydantic-ai python -c ' import asyncio from pydantic_ai import Agent from pydantic_ai.mcp import MCPServerStdio server = MCPServerStdio( "deno", args=[ "run", "-N", "-R=node_modules", "-W=node_modules", "--node-modules-dir=auto", "jsr:@pydantic/mcp-run-python", "stdio", ], ) agent = Agent("claude-3-5-haiku-latest", mcp_servers=[server]) async def main(): async with agent.run_mcp_servers(): result = await agent.run("How many days between 2000-01-01 and 2025-03-18?") print(result.output) asyncio.run(main())'

I ran that just now and got:

The number of days between January 1st, 2000 and March 18th, 2025 is 9,208 days.

I thoroughly enjoy how tools like uv and Deno enable throwing together shell one-liner demos like this one.

Here's an extended version of this example which adds pretty-printed logging of the messages exchanged with the LLM to illustrate exactly what happened. The most important piece is this tool call where Claude 3.5 Haiku asks for Python code to be executed my the MCP server:

ToolCallPart( tool_name='run_python_code', args={ 'python_code': ( 'from datetime import date\n' '\n' 'date1 = date(2000, 1, 1)\n' 'date2 = date(2025, 3, 18)\n' '\n' 'days_between = (date2 - date1).days\n' 'print(f"Number of days between {date1} and {date2}: {days_between}")' ), }, tool_call_id='toolu_01TXXnQ5mC4ry42DrM1jPaza', part_kind='tool-call', )

I also managed to run it against Mistral Small 3.1 (15GB) running locally using Ollama (I had to add "Use your python tool" to the prompt to get it to work):

ollama pull mistral-small3.1:24b uv run --with devtools --with pydantic-ai python -c ' import asyncio from devtools import pprint from pydantic_ai import Agent, capture_run_messages from pydantic_ai.models.openai import OpenAIModel from pydantic_ai.providers.openai import OpenAIProvider from pydantic_ai.mcp import MCPServerStdio server = MCPServerStdio( "deno", args=[ "run", "-N", "-R=node_modules", "-W=node_modules", "--node-modules-dir=auto", "jsr:@pydantic/mcp-run-python", "stdio", ], ) agent = Agent( OpenAIModel( model_name="mistral-small3.1:latest", provider=OpenAIProvider(base_url="http://localhost:11434/v1"), ), mcp_servers=[server], ) async def main(): with capture_run_messages() as messages: async with agent.run_mcp_servers(): result = await agent.run("How many days between 2000-01-01 and 2025-03-18? Use your python tool.") pprint(messages) print(result.output) asyncio.run(main())'

Here's the full output including the debug logs.

openai/codex. Just released by OpenAI, a "lightweight coding agent that runs in your terminal". Looks like their version of Claude Code, though unlike Claude Code Codex is released under an open source (Apache 2) license.

Here's the main prompt that runs in a loop, which starts like this:

You are operating as and within the Codex CLI, a terminal-based agentic coding assistant built by OpenAI. It wraps OpenAI models to enable natural language interaction with a local codebase. You are expected to be precise, safe, and helpful.

You can:

- Receive user prompts, project context, and files.

- Stream responses and emit function calls (e.g., shell commands, code edits).

- Apply patches, run commands, and manage user approvals based on policy.

- Work inside a sandboxed, git-backed workspace with rollback support.

- Log telemetry so sessions can be replayed or inspected later.

- More details on your functionality are available at codex --help

The Codex CLI is open-sourced. Don't confuse yourself with the old Codex language model built by OpenAI many moons ago (this is understandably top of mind for you!). Within this context, Codex refers to the open-source agentic coding interface. [...]

I like that the prompt describes OpenAI's previous Codex language model as being from "many moons ago". Prompt engineering is so weird.

Since the prompt says that it works "inside a sandboxed, git-backed workspace" I went looking for the sandbox. On macOS it uses the little-known sandbox-exec process, part of the OS but grossly under-documented. The best information I've found about it is this article from 2020, which notes that man sandbox-exec lists it as deprecated. I didn't spot evidence in the Codex code of sandboxes for other platforms.

Not all AI-assisted programming is vibe coding (but vibe coding rocks)

Vibe coding is having a moment. The term was coined by Andrej Karpathy just a few weeks ago (on February 6th) and has since been featured in the New York Times, Ars Technica, the Guardian and countless online discussions.

[... 1,486 words]2024

OpenStreetMap embed URL.

I just found out OpenStreetMap have a "share" button which produces HTML for an iframe targetting https://www.openstreetmap.org/export/embed.html, making it easy to drop an OpenStreetMap map onto any web page that allows iframes.

As far as I can tell the supported parameters are:

bbox=then min longitude, min latitude, max longitude, max latitudemarker=optional latitude, longitude coordinate for a marker (only a single marker is supported)layer=mapnik- other values I've found that work arecyclosm,cyclemap,transportmapandhot(for humanitarian)

Here's HTML for embedding this on a page using a sandboxed iframe - the allow-scripts is necessary for the map to display.

<iframe

sandbox="allow-scripts"

style="border: none; width: 100%; height: 20em;"

src="https://www.openstreetmap.org/export/embed.html?bbox=-122.613%2C37.431%2C-122.382%2C37.559&layer=mapnik&marker=37.495%2C-122.497"

></iframe>

Thanks to this post I learned that iframes are rendered correctly in NetNewsWire, NewsExplorer, NewsBlur and Feedly on Android.

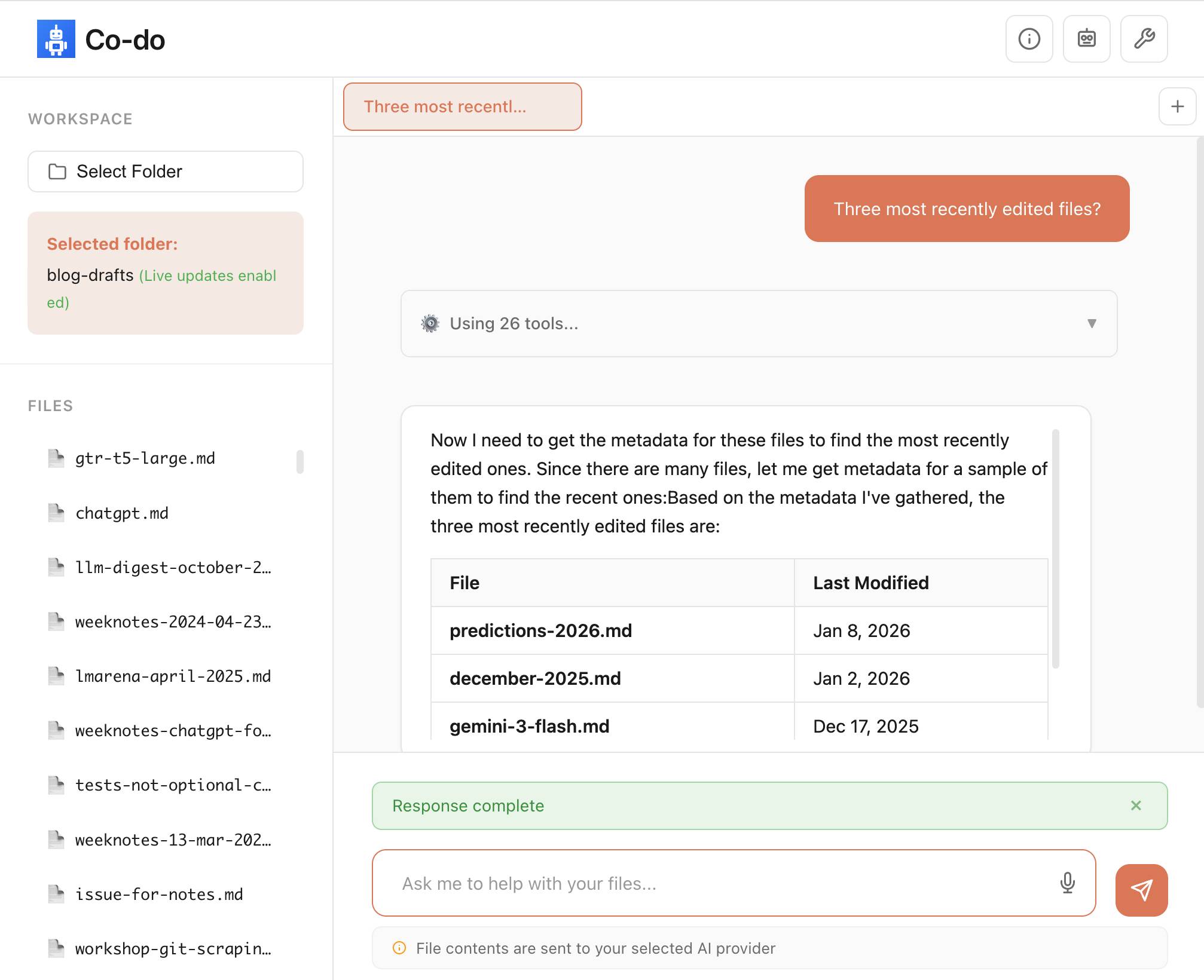

open-interpreter (via) This "natural language interface for computers" open source ChatGPT Code Interpreter alternative has been around for a while, but today I finally got around to trying it out.

Here's how I ran it (without first installing anything) using uv:

uvx --from open-interpreter interpreter

The default mode asks you for an OpenAI API key so it can use gpt-4o - there are a multitude of other options, including the ability to use local models with interpreter --local.

It runs in your terminal and works by generating Python code to help answer your questions, asking your permission to run it and then executing it directly on your computer.

I pasted in an API key and then prompted it with this:

find largest files on my desktop

Here's the full transcript.

Since code is run directly on your machine there are all sorts of ways things could go wrong if you don't carefully review the generated code before hitting "y". The team have an experimental safe mode in development which works by scanning generated code with semgrep. I'm not convinced by that approach, I think executing code in a sandbox would be a much more robust solution here - but sandboxing Python is still a very difficult problem.

They do at least have an experimental Docker integration.

Cerebras Coder (via) Val Town founder Steve Krouse has been building demos on top of the Cerebras API that runs Llama3.1-70b at 2,000 tokens/second.

Having a capable LLM with that kind of performance turns out to be really interesting. Cerebras Coder is a demo that implements Claude Artifact-style on-demand JavaScript apps, and having it run at that speed means changes you request are visible within less than a second:

Steve's implementation (created with the help of Townie, the Val Town code assistant) demonstrates the simplest possible version of an iframe sandbox:

<iframe

srcDoc={code}

sandbox="allow-scripts allow-modals allow-forms allow-popups allow-same-origin allow-top-navigation allow-downloads allow-presentation allow-pointer-lock"

/>

Where code is populated by a setCode(...) call inside a React component.

The most interesting applications of LLMs continue to be where they operate in a tight loop with a human - this can make those review loops potentially much faster and more productive.

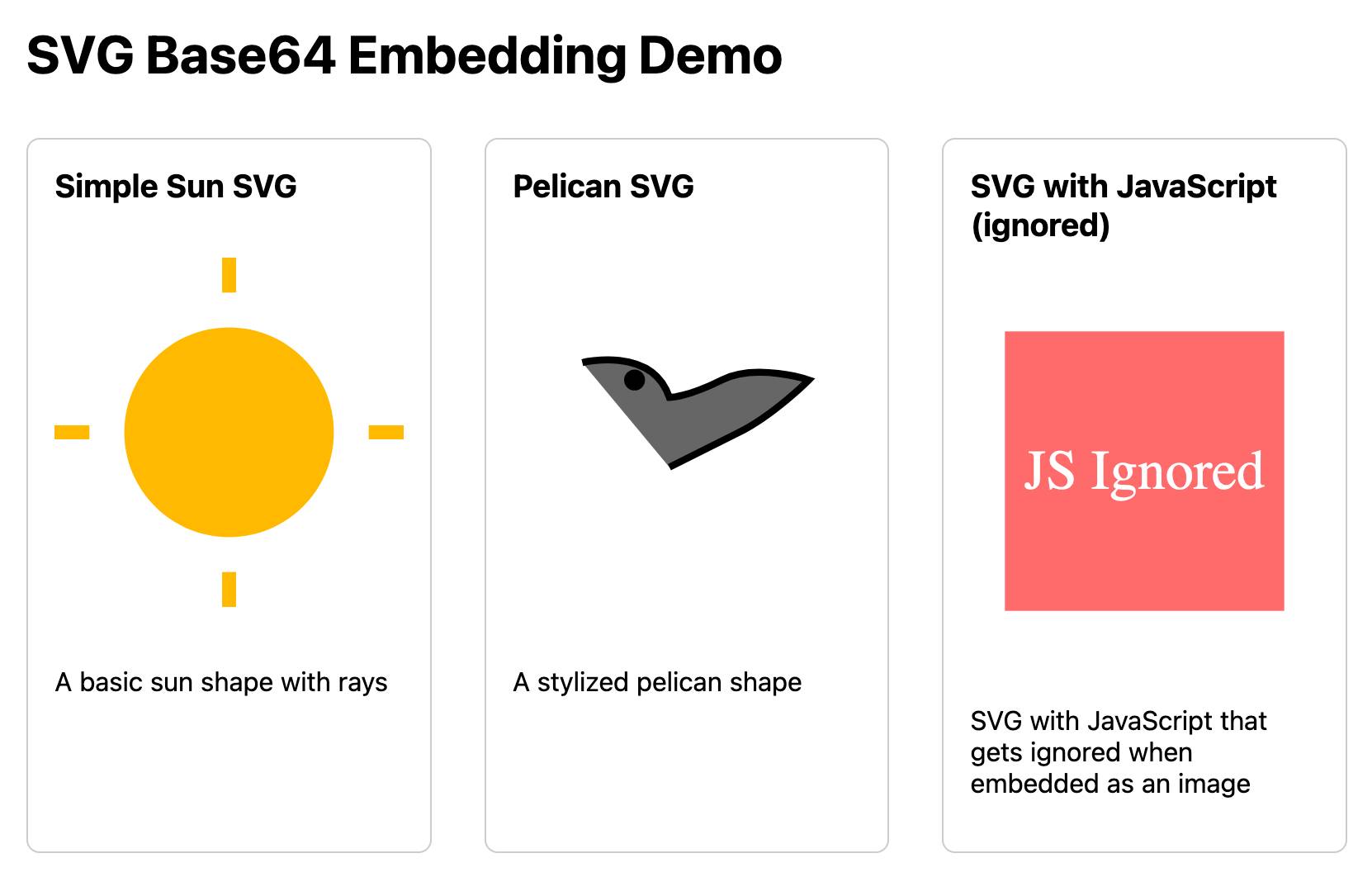

Mastodon discussion about sandboxing SVG data. I asked this on Mastodon and got some really useful replies:

How hard is it to process untrusted SVG data to strip out any potentially harmful tags or attributes (like stuff that might execute JavaScript)?

The winner for me turned out to be the humble <img src=""> tag. SVG images that are rendered in an image have all dynamic functionality - including embedded JavaScript - disabled by default, and that's something that's directly included in the spec:

2.2.6. Secure static mode

This processing mode is intended for circumstances where an SVG document is to be used as a non-animated image that is not allowed to resolve external references, and which is not intended to be used as an interactive document. This mode might be used where image support has traditionally been limited to non-animated raster images (such as JPEG and PNG.)

[...]

'image' references

An SVG embedded within an 'image' element must be processed in secure animated mode if the embedding document supports declarative animation, or in secure static mode otherwise.

The same processing modes are expected to be used for other cases where SVG is used in place of a raster image, such as an HTML 'img' element or in any CSS property that takes an

data type. This is consistent with HTML's requirement that image sources must reference "a non-interactive, optionally animated, image resource that is neither paged nor scripted" [HTML]

This also works for SVG data that's presented in a <img src="data:image/svg+xml;base64,... attribute. I had Claude help spin me up this interactive demo:

Build me an artifact - just HTML, no JavaScript - which demonstrates embedding some SVG files using img src= base64 URIs

I want three SVGs - one of the sun, one of a pelican and one that includes some tricky javascript things which I hope the img src= tag will ignore

If you right click and "open in a new tab" on the JavaScript-embedding SVG that script will execute, showing an alert. You can click the image to see another alert showing location.href and document.cookie which should confirm that the base64 image is not treated as having the same origin as the page itself.

How Anthropic built Artifacts. Gergely Orosz interviews five members of Anthropic about how they built Artifacts on top of Claude with a small team in just three months.

The initial prototype used Streamlit, and the biggest challenge was building a robust sandbox to run the LLM-generated code in:

We use iFrame sandboxes with full-site process isolation. This approach has gotten robust over the years. This protects users' main Claude.ai browsing session from malicious artifacts. We also use strict Content Security Policies (CSPs) to enforce limited and controlled network access.

Artifacts were launched in general availability yesterday - previously you had to turn them on as a preview feature. Alex Albert has a 14 minute demo video up on Twitter showing the different forms of content they can create, including interactive HTML apps, Markdown, HTML, SVG, Mermaid diagrams and React Components.

The first four Val Town runtimes

(via)

Val Town solves one of my favourite technical problems: how to run untrusted code in a safe sandbox. They're on their fourth iteration of this now, currently using a Node.js application that launches Deno sub-processes using the node-deno-vm npm package and runs code in those, taking advantage of the Deno sandboxing mechanism and terminating processes that take too long in order to protect against while(true) style attacks.

2023

In general my approach to running arbitrary untrusted code is 20% sandboxing and 80% making sure that it’s an extremely low value attack target so it’s not worth trying to break in.

Programs are terminated after 1 second of runtime, they run in a container with no network access, and the machine they’re running on has no sensitive data on it and a very small CPU.

Cyber (via) “Cyber is a new language for fast, efficient, and concurrent scripting.” Lots of interesting ideas in here, but the one that really caught my eye is that its designed to be easily embedded into other languages and “will allow the host to insert gas mileage checks in user scripts. This allows the host to control how long a script can run”—my dream feature for implementing a safe, sandboxed extension mechanism! Cyber is implemented using Zig and LLVM.

Python Sandbox in Web Assembly (via) Jim Kring responded to my questions on Mastodon about running Python in a WASM sandbox by building this repo, which demonstrates using wasmer-python to run a build of Python 3.6 compiled to WebAssembly, complete with protected access to a sandbox directory.