107 posts tagged “databases”

2025

Sometimes a service with a free plan will decide to stop supporting it. I understand why this happens, but I'm often disappointed at the treatment of existing user's data. It's easy to imagine users forgetting about their old accounts, missing the relevant emails and then discovering too late that their data is gone.

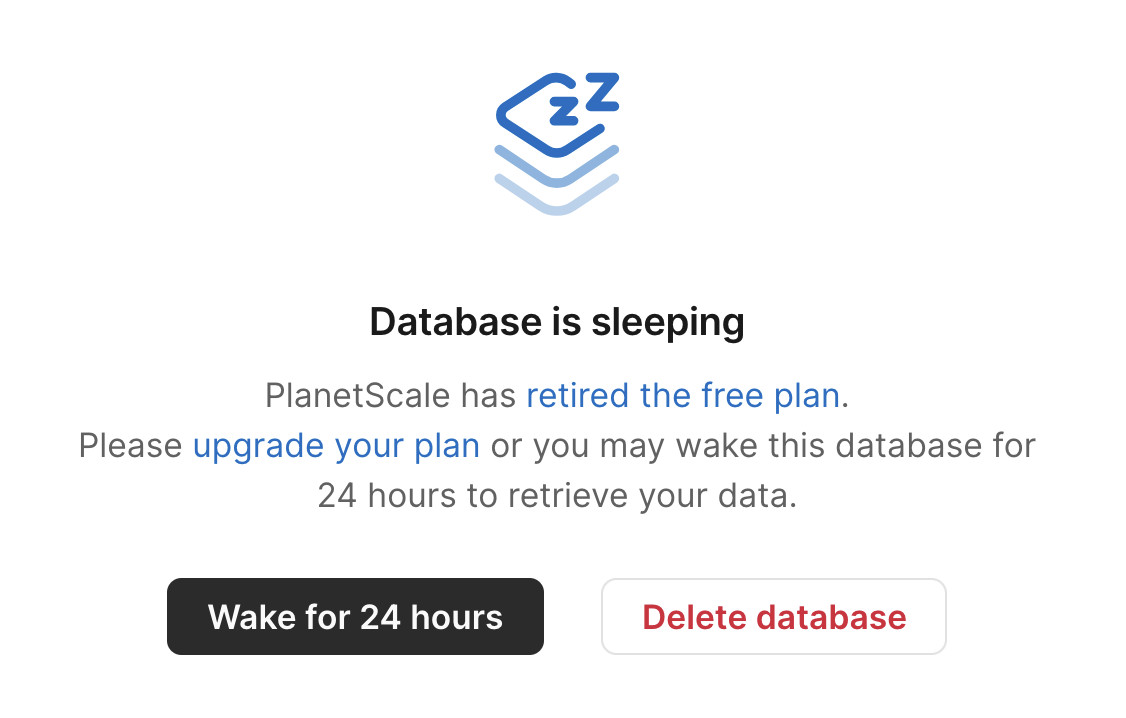

Inspired by today's news about PlanetScale PostgreSQL I signed into PlanetScale and found I had a long-forgotten trial account there with a three-year-old database on their free tier. That free tier was retired in March 2024.

Here's the screen that greeted me in their control panel:

What a great way to handle retiring a free plan! My data is still there, and I have the option to spin up a database for 24 hours to help get it back out again.

Announcing PlanetScale for Postgres. PlanetScale formed in 2018 to build a commercial offering on top of the Vitess MySQL sharding open source project, which was originally released by YouTube in 2012. The PlanetScale founders were the co-creators and maintainers of Vitess.

Today PlanetScale are announcing a private preview of their new horizontally sharded PostgreSQL solution, due to "overwhelming" demand.

Notably, it doesn't use Vitess under the hood:

Vitess is one of PlanetScale’s greatest strengths [...] We have made explicit sharding accessible to hundreds of thousands of users and it is time to bring this power to Postgres. We will not however be using Vitess to do this.

Vitess’ achievements are enabled by leveraging MySQL’s strengths and engineering around its weaknesses. To achieve Vitess’ power for Postgres we are architecting from first principles.

Meanwhile, on June 10th Supabase announced that they had hired Vitess co-creator Sugu Sougoumarane to help them build "Multigres: Vitess for Postgres". Sugu said:

For some time, I've been considering a Vitess adaptation for Postgres, and this feeling had been gradually intensifying. The recent explosion in the popularity of Postgres has fueled this into a full-blown obsession. [...]

The project to address this problem must begin now, and I'm convinced that Vitess provides the most promising foundation.

I remember when MySQL was an order of magnitude more popular than PostgreSQL, and Heroku's decision to only offer PostgreSQL back in 2007 was a surprising move. The vibes have certainly shifted.

ClickHouse gets lazier (and faster): Introducing lazy materialization (via) Tom Schreiber describe's the latest optimization in ClickHouse, and in the process explores a whole bunch of interesting characteristics of columnar datastores generally.

As I understand it, the new "lazy materialization" feature means that if you run a query like this:

select id, big_col1, big_col2

from big_table order by rand() limit 5

Those big_col1 and big_col2 columns won't be read from disk for every record, just for the five that are returned. This can dramatically improve the performance of queries against huge tables - for one example query ClickHouse report a drop from "219 seconds to just 139 milliseconds—with 40× less data read and 300× lower memory usage."

I'm linking to this mainly because the article itself is such a detailed discussion of columnar data patterns in general. It caused me to update my intuition for how queries against large tables can work on modern hardware. This query for example:

SELECT helpful_votes

FROM amazon.amazon_reviews

ORDER BY helpful_votes DESC

LIMIT 3;

Can run in 70ms against a 150 million row, 70GB table - because in a columnar database you only need to read that helpful_votes integer column which adds up to just 600MB of data, and sorting 150 million integers on a decent machine takes no time at all.

I Went To SQL Injection Court (via) Thomas Ptacek talks about his ongoing involvement as an expert witness in an Illinois legal battle lead by Matt Chapman over whether a SQL schema (e.g. for the CANVAS parking ticket database) should be accessible to Freedom of Information (FOIA) requests against the Illinois state government.

They eventually lost in the Illinois Supreme Court, but there's still hope in the shape of IL SB0226, a proposed bill that would amend the FOIA act to ensure "that the public body shall provide a sufficient description of the structures of all databases under the control of the public body to allow a requester to request the public body to perform specific database queries".

Thomas posted this comment on Hacker News:

Permit me a PSA about local politics: engaging in national politics is bleak and dispiriting, like being a gnat bouncing off the glass plate window of a skyscraper. Local politics is, by contrast, extremely responsive. I've gotten things done --- including a law passed --- in my spare time and at practically no expense (drastically unlike national politics).

What to do about SQLITE_BUSY errors despite setting a timeout

(via)

Bert Hubert takes on the challenge of explaining SQLite's single biggest footgun: in WAL mode you may see SQLITE_BUSY errors even when you have a generous timeout set if a transaction attempts to obtain a write lock after initially running at least one SELECT. The fix is to use BEGIN IMMEDIATE if you know your transaction is going to make a write.

Bert provides the clearest explanation I've seen yet of why this is necessary:

When the transaction on the left wanted to upgrade itself to a read-write transaction, SQLite could not allow this since the transaction on the right might already have made changes that the transaction on the left had not yet seen.

This in turn means that if left and right transactions would commit sequentially, the result would not necessarily be what would have happened if all statements had been executed sequentially within the same transaction.

I've written about this a few times before, so I just started a sqlite-busy tag to collect my notes together on a single page.

2024

DSQL Vignette: Reads and Compute. Marc Brooker is one of the engineers behind AWS's new Aurora DSQL horizontally scalable database. Here he shares all sorts of interesting details about how it works under the hood.

The system is built around the principle of separating storage from compute: storage uses S3, while compute runs in Firecracker:

Each transaction inside DSQL runs in a customized Postgres engine inside a Firecracker MicroVM, dedicated to your database. When you connect to DSQL, we make sure there are enough of these MicroVMs to serve your load, and scale up dynamically if needed. We add MicroVMs in the AZs and regions your connections are coming from, keeping your SQL query processor engine as close to your client as possible to optimize for latency.

We opted to use PostgreSQL here because of its pedigree, modularity, extensibility, and performance. We’re not using any of the storage or transaction processing parts of PostgreSQL, but are using the SQL engine, an adapted version of the planner and optimizer, and the client protocol implementation.

The system then provides strong repeatable-read transaction isolation using MVCC and EC2's high precision clocks, enabling reads "as of time X" including against nearby read replicas.

The storage layer supports index scans, which means the compute layer can push down some operations allowing it to load a subset of the rows it needs, reducing round-trips that are affected by speed-of-light latency.

The overall approach here is disaggregation: we’ve taken each of the critical components of an OLTP database and made it a dedicated service. Each of those services is independently horizontally scalable, most of them are shared-nothing, and each can make the design choices that is most optimal in its domain.

Introducing Amazon Aurora DSQL (via) New, weird-shaped database from AWS. It's (loosely) PostgreSQL compatible, claims "virtually unlimited scale" and can be set up as a single-region cluster or as a multi-region setup that somehow supports concurrent reads and writes across all regions. I'm hoping they publish technical details on how that works at some point in the future (update: they did), right now they just say this:

When you create a multi-Region cluster, Aurora DSQL creates another cluster in a different Region and links them together. Adding linked Regions makes sure that all changes from committed transactions are replicated to the other linked Regions. Each linked cluster has a Regional endpoint, and Aurora DSQL synchronously replicates writes across Regions, enabling strongly consistent reads and writes from any linked cluster.

Here's the list of unsupported PostgreSQL features - most notably views, triggers, sequences, foreign keys and extensions. A single transaction can also modify only up to 10,000 rows.

No pricing information yet (it's in a free preview) but it looks like this one may be true scale-to-zero, unlike some of their other recent "serverless" products - Amazon Aurora Serverless v2 has a baseline charge no matter how heavily you are using it. (Update: apparently that changed on 20th November 2024 when they introduced an option to automatically pause a v2 serverless instance, which then "takes less than 15 seconds to resume".)

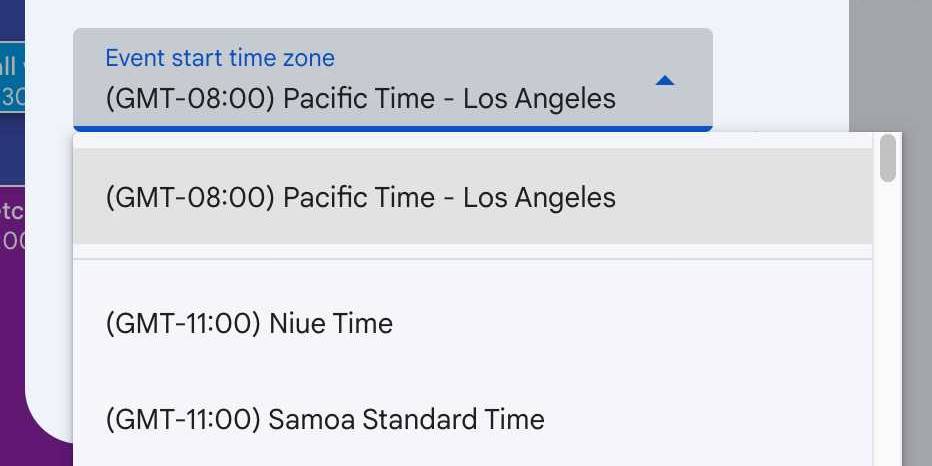

Storing times for human events

I’ve worked on various event websites in the past, and one of the unintuitively difficult problems that inevitably comes up is the best way to store the time that an event is happening. Based on that past experience, here’s my current recommendation.

[... 1,676 words]Whither CockroachDB? (via) CockroachDB - previously Apache 2.0, then BSL 1.1 - announced on Wednesday that they were moving to a source-available license.

Oxide use CockroachDB for their product's control plane database. That software is shipped to end customers in an Oxide rack, and it's unacceptable to Oxide for their customers to think about the CockroachDB license.

Oxide use RFDs - Requests for Discussion - internally, and occasionally publish them (see rfd1) using their own custom software.

They chose to publish this RFD that they wrote in response to the CockroachDB license change, describing in detail the situation they are facing and the options they considered.

Since CockroachDB is a critical component in their stack which they have already patched in the past, they're opting to maintain their own fork of a recent Apache 2.0 licensed version:

The immediate plan is to self-support on CochroachDB 22.1 and potentially CockroachDB 22.2; we will not upgrade CockroachDB beyond 22.2. [...] This is not intended to be a community fork (we have no current intent to accept outside contributions); we will make decisions in this repository entirely around our own needs. If a community fork emerges based on CockroachDB 22.x, we will support it (and we will specifically seek to get our patches integrated), but we may or may not adopt it ourselves: we are very risk averse with respect to this database and we want to be careful about outsourcing any risk decisions to any entity outside of Oxide.

The full document is a fascinating read - as Kelsey Hightower said:

This is engineering at its finest and not a single line of code was written.

A write-ahead log is not a universal part of durability (via) Phil Eaton uses pseudo code to provide a clear description of how write-ahead logs in transactional database systems work, useful for understanding the tradeoffs they make and the guarantees they can provided.

I particularly liked the pseudo code explanation of group commits, where clients block waiting for their commit to be acknowledged as part of a batch of writes flushed to disk.

DuckDB 1.0 (via) Six years in the making. The most significant feature in this milestone is stability of the file format: previous releases often required files to be upgraded to work with the new version.

This release also aspires to provide stability for both the SQL dialect and the C API, though these may still change with sufficient warning in the future.

Why SQLite Uses Bytecode (via) Brand new SQLite architecture documentation by D. Richard Hipp explaining the trade-offs between a bytecode based query plan and a tree of objects.

SQLite uses the bytecode approach, which provides an important characteristic that SQLite can very easily execute queries incrementally—stopping after each row, for example. This is more useful for a local library database than for a network server where the assumption is that the entire query will be executed before results are returned over the wire.

Optimizing SQLite for servers (via) Sylvain Kerkour's comprehensive set of lessons learned running SQLite for server-based applications.

There's a lot of useful stuff in here, including detailed coverage of the different recommended PRAGMA settings.

There was also a tip I haven't seen before about BEGIN IMMEDIATE transactions:

By default, SQLite starts transactions in

DEFERREDmode: they are considered read only. They are upgraded to a write transaction that requires a database lock in-flight, when query containing a write/update/delete statement is issued.The problem is that by upgrading a transaction after it has started, SQLite will immediately return a

SQLITE_BUSYerror without respecting thebusy_timeoutpreviously mentioned, if the database is already locked by another connection.This is why you should start your transactions with

BEGIN IMMEDIATEinstead of onlyBEGIN. If the database is locked when the transaction starts, SQLite will respectbusy_timeout.

How Figma’s databases team lived to tell the scale (via) The best kind of scaling war story:

"Figma’s database stack has grown almost 100x since 2020. [...] In 2020, we were running a single Postgres database hosted on AWS’s largest physical instance, and by the end of 2022, we had built out a distributed architecture with caching, read replicas, and a dozen vertically partitioned databases."

I like the concept of "colos", their internal name for sharded groups of related tables arranged such that those tables can be queried using joins.

Also smart: separating the migration into "logical sharding" - where queries all still run against a single database, even though they are logically routed as if the database was already sharded - followed by "physical sharding" where the data is actually copied to and served from the new database servers.

Logical sharding was implemented using PostgreSQL views, which can accept both reads and writes:

CREATE VIEW table_shard1 AS SELECT * FROM table

WHERE hash(shard_key) >= min_shard_range AND hash(shard_key) < max_shard_range)

The final piece of the puzzle was DBProxy, a custom PostgreSQL query proxy written in Go that can parse the query to an AST and use that to decide which shard the query should be sent to. Impressively it also has a scatter-gather mechanism, so select * from table can be sent to all shards at once and the results combined back together again.

S3 is files, but not a filesystem (via) Cal Paterson helps some concepts click into place for me: S3 imitates a file system but has a number of critical missing features, the most important of which is the lack of partial updates. Any time you want to modify even a few bytes in a file you have to upload and overwrite the entire thing. Almost every database system is dependent on partial updates to function, which is why there are so few databases that can use S3 directly as a backend storage mechanism.

Endatabas (via) Endatabas is “an open source immutable database”—also described as “SQL document database with full history”.

It uses a variant of SQL which allows you to insert data into tables that don’t exist yet (they’ll be created automatically) then run standard select queries, joins etc. It maintains a full history of every record and supports the recent SQL standard “FOR SYSTEM_TIME AS OF” clause for retrieving historical records as they existed at a specified time (it defaults to the most recent versions).

It’s written in Common Lisp plus a bit of Rust, and includes Docker images for running the server and client libraries in JavaScript and Python. The on-disk storage format is Apache Arrow, the license is AGPL and it’s been under development for just over a year.

It’s also a document database: you can insert JSON-style nested objects directly into a table, and query them with path expressions like “select users.friends[1] from users where id = 123;”

They have a WebAssembly version and a nice getting started tutorial which you can try out directly in your browser.

Their “Why?” page lists full history, time travel queries, separation of storage from compute, schemaless tables and columnar storage as the five pillars that make up their product. I think it’s a really interesting amalgamation of ideas.

Announcing DuckDB 0.10.0.

Somewhat buried in this announcement: DuckDB has Fixed-Length Arrays now, along with array_cross_product(a1, a2), array_cosine_similarity(a1, a2) and array_inner_product(a1, a2) functions.

This means you can now use DuckDB to find related content (and other tricks) using vector embeddings!

Also notable:

DuckDB can now attach MySQL, Postgres, and SQLite databases in addition to databases stored in its own format. This allows data to be read into DuckDB and moved between these systems in a convenient manner, as attached databases are fully functional, appear just as regular tables, and can be updated in a safe, transactional manner.

Before we even started writing the database, we first wrote a fully-deterministic event-based network simulation that our database could plug into. This system let us simulate an entire cluster of interacting database processes, all within a single-threaded, single-process application, and all driven by the same random number generator. We could run this virtual cluster, inject network faults, kill machines, simulate whatever crazy behavior we wanted, and see how it reacted. Best of all, if one particular simulation run found a bug in our application logic, we could run it over and over again with the same random seed, and the exact same series of events would happen in the exact same order. That meant that even for the weirdest and rarest bugs, we got infinity “tries” at figuring it out, and could add logging, or do whatever else we needed to do to track it down.

[...] At FoundationDB, once we hit the point of having ~zero bugs and confidence that any new ones would be found immediately, we entered into this blessed condition and we flew.

[...] We had built this sophisticated testing system to make our database more solid, but to our shock that wasn’t the biggest effect it had. The biggest effect was that it gave our tiny engineering team the productivity of a team 50x its size.

— Will Wilson, on FoundationDB

SQLite 3.45. Released today. The big new feature is JSONB support, a new, specific-to-SQLite binary internal representation of JSON which can provide up to a 3x performance improvement for JSON-heavy operations, plus a 5-10% saving it terms of bytes stored on disk.

2023

Stripe: Online migrations at scale (via) This 2017 blog entry from Jacqueline Xu at Stripe provides a very clear description of the “dual writes” pattern for applying complex data migrations without downtime: dual write to new and old tables, update the read paths, update the write paths and finally remove the now obsolete data—illustrated with an example of upgrading customers from having a single to multiple subscriptions.

Database Migrations. Vadim Kravcenko provides a useful, in-depth description of the less obvious challenges of applying database migrations successfully. Vadim uses and likes Django’s migrations (as do I) but notes that running them at scale still involves a number of thorny challenges.

The biggest of these, which I’ve encountered myself multiple times, is that if you want truly zero downtime deploys you can’t guarantee that your schema migrations will be deployed at the exact same instant as changes you make to your application code.

This means all migrations need to be forward-compatible: you need to apply a schema change in a way that your existing code will continue to work error-free, then ship the related code change as a separate operation.

Vadim describes what this looks like in detail for a number of common operations: adding a field, removing a field and changing a field that has associated business logic implications. He also discusses the importance of knowing when to deploy a dual-write strategy.

Upsert in SQL (via) Anton Zhiyanov is currently on a one-man quest to write detailed documentation for all of the fundamental SQL operations, comparing and contrasting how they work across multiple engines, generally with interactive examples.

Useful tips in here on why “insert... on conflict” is usually a better option than “insert or replace into” because the latter can perform a delete and then an insert, firing triggers that you may not have wanted to be fired.

2022

JSON Changelog with SQLite (via) One of my favourite database challenges is how to track changes to rows over time. This is a neat recipe from 2018 which uses SQLite triggers and the SQLite JSON functions to serialize older versions of the rows and store them in TEXT columns.

Querying Postgres Tables Directly From DuckDB (via) I learned a lot of interesting PostgreSQL tricks from this write-up of the new DuckDB feature that allows it to run queries against PostgreSQL servers directly. It works using COPY (SELECT ...) TO STDOUT (FORMAT binary) which writes rows to the protocol stream in efficient binary format, but splits the table being read into parallel fetches against page ranges and uses SET TRANSACTION SNAPSHOT ... in those parallel queries to ensure they see the same transactional snapshot of the database.

Introducing LiteFS (via) LiteFS is the new SQLite replication solution from Fly, now ready for beta testing. It’s from the same author as Litestream but has a very different architecture; LiteFS works by implementing a custom FUSE filesystem which spies on SQLite transactions being written to the journal file and forwards them on to other nodes in the cluster, providing full read-replication. The signature Litestream feature of streaming a backup to S3 should be coming within the next few months.

How the SQLite Virtual Machine Works. The latest entry in Ben Johnson’s series about SQLite internals.

Notes on the SQLite DuckDB paper

SQLite: Past, Present, and Future is a newly published paper authored by Kevin P. Gaffney, Martin Prammer and Jignesh M. Patel from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and D. Richard Hipp, Larry Brasfield and Dan Kennedy from the core SQLite engineering team.

[... 1,021 words]How SQLite Scales Read Concurrency (via) Ben Johnson’s series on SQLite internals continues—this time with a detailed explanation of how the SQLite WAL (Write-Ahead Log) is implemented.

Turning SQLite into a distributed database (via) Heyang Zhou introduces mvSQLite, his brand new open source “SQLite-compatible distributed database” built in Rust on top of Apple’s FoundationDB. This is a very promising looking new entry into the distributed/replicated SQLite space: FoundationDB was designed to provide low-level primitives that tools like this could build on top of.

SQLite Internals: Pages & B-trees (via) Ben Johnson provides a delightfully clear introduction to SQLite internals, describing the binary format used to store rows on disk and how SQLite uses 4KB pages for both row storage and for the b-trees used to look up records.