Crowdsourced document analysis and MP expenses

20th December 2009

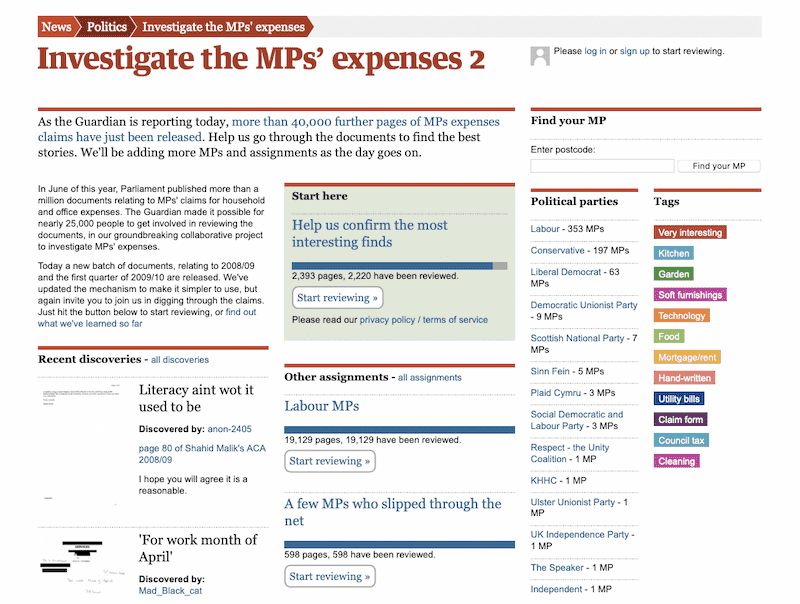

As you may have heard, the UK government released a fresh batch of MP expenses documents a week ago on Thursday. I spent that week working with a small team at Guardian HQ to prepare for the release. Here’s what we built:

http://mps-expenses2.guardian.co.uk/ Updated March 2021: all links now go to the Internet Archive

It’s a crowdsourcing application that asks the public to help us dig through and categorise the enormous stack of documents—around 30,000 pages of claim forms, scanned receipts and hand-written letters, all scanned and published as PDFs.

This is the second time we’ve tried this—the first was back in June, and can be seen at mps-expenses.guardian.co.uk. Last week’s attempt was an opportunity to apply the lessons we learnt the first time round.

Writing crowdsourcing applications in a newspaper environment is a fascinating challenge. Projects have very little notice—I heard about the new document release the Thursday before giving less than a week to put everything together. In addition to the fast turnaround for the application itself, the 48 hours following the release are crucial. The news cycle moves fast, so if the application launches but we don’t manage to get useful data out of it quickly the story will move on before we can impact it.

ScaleCamp on the Friday meant that development work didn’t properly kick off until Monday morning. The bulk of the work was performed by two server-side developers, one client-side developer, one designer and one QA on Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday. The Guardian operations team deftly handled our EC2 configuration and deployment, and we had some extra help on the day from other members of the technology department. After launch we also had a number of journalists helping highlight discoveries and dig through submissions.

The system was written using Django, MySQL (InnoDB), Redis and memcached.

Asking the right question

The biggest mistake we made the first time round was that we asked the wrong question. We tried to get our audience to categorise documents as either “claims” or “receipts” and to rank them as “not interesting”, “a bit interesting”, “interesting but already known” and “someone should investigate this”. We also asked users to optionally enter any numbers they saw on the page as categorised “line items”, with the intention of adding these up later.

The line items, with hindsight, were a mistake. 400,000 documents makes for a huge amount of data entry and for the figures to be useful we would need to confirm their accuracy. This would mean yet more rounds of crowdsourcing, and the job was so large that the chance of getting even one person to enter line items for each page rapidly diminished as the news story grew less prominent.

The categorisations worked reasonably well but weren’t particularly interesting—knowing if a document is a claim or receipt is useful only if you’re going to collect line items. The “investigate this” button worked very well though.

We completely changed our approach for the new system. We dropped the line item task and instead asked our users to categories each page by applying one or more tags, from a small set that our editors could control. This gave us a lot more flexibility—we changed the tags shortly before launch based on the characteristics of the documents—and had the potential to be a lot more fun as well. I’m particularly fond of the “hand-written” tag, which has highlighted some lovely examples of correspondence between MPs and the expenses office.

Sticking to an editorially assigned set of tags provided a powerful tool for directing people’s investigations, and also ensured our users didn’t start creating potentially libelous tags of their own.

Breaking it up in to assignments

For the first project, everyone worked together on the same task to review all of the documents. This worked fine while the document set was small, but once we had loaded in 400,000+ pages the progress bar become quite depressing.

This time round, we added a new concept of "assignments". Each assignment consisted of the set of pages belonging to a specified list of MPs, documents or political parties. Assignments had a threshold, so we could specify that a page must be reviewed by at least X people before it was considered reviewed. An editorial tool let us feature one "main" assignment and several alternative assignments right on the homepage.

Clicking “start reviewing” on an assignment sets a cookie for that assignment, and adds the assignment’s progress bar to the top of the review interface. New pages are selected at random from the set of unreviewed pages in that assignment.

The assignments system proved extremely effective. We could use it to direct people to the highest value documents (our top hit list of interesting MPs, or members of the shadow cabinet) while still allowing people with specific interests to pick an alternative task.

Get the button right!

Having run two crowdsourcing projects I can tell you this: the single most important piece of code you will write is the code that gives someone something new to review. Both of our projects had big “start reviewing” buttons. Both were broken in different ways.

The first time round, the mistakes were around scalability. I used a SQL “ORDER BY RAND()” statement to return the next page to review. I knew this was an inefficient operation, but I assumed that it wouldn’t matter since the button would only be clicked occasionally.

Something like 90% of our database load turned out to be caused by that one SQL statement, and it only got worse as we loaded more pages in to the system. This caused multiple site slow downs and crashes until we threw together a cron job that pushed 1,000 unreviewed page IDs in to memcached and made the button pick one of those at random.

This solved the performance problem, but meant that our user activity wasn’t nearly as well targeted. For optimum efficiency you really want everyone to be looking at a different page—and a random distribution is almost certainly the easiest way to achieve that.

The second time round I turned to my new favourite in-memory data structure server, redis, and its SRANDMEMBER command (a feature I requested a while ago with this exact kind of project in mind). The system maintains a redis set of all IDs that needed to be reviewed for an assignment to be complete, and a separate set of IDs of all pages had been reviewed. It then uses redis set intersection (the SDIFFSTORE command) to create a set of unreviewed pages for the current assignment and then SRANDMEMBER to pick one of those pages.

This is where the bug crept in. Redis was just being used as an optimisation—the single point of truth for whether a page had been reviewed or not stayed as MySQL. I wrote a couple of Django management commands to repopulate the denormalised Redis sets should we need to manually modify the database. Unfortunately I missed some—the sets that tracked what pages were available in each document. The assignment generation code used an intersection of these sets to create the overall set of documents for that assignment. When we deleted some pages that had accidentally been imported twice I failed to update those sets.

This meant the “next page” button would occasionally turn up a page that didn’t exist. I had some very poorly considered fallback logic for that—if the random page didn’t exist, the system would return the first page in that assignment instead. Unfortunately, this meant that when the assignment was down to the last four non-existent pages every single user was directed to the same page—which subsequently attracted well over a thousand individual reviews.

Next time, I’m going to try and make the “next” button completely bullet proof! I’m also going to maintain a “denormalisation dictionary” documenting every denormalisation in the system in detail—such a thing would have saved me several hours of confused debugging.

Exposing the results

The biggest mistake I made last time was not getting the data back out again fast enough for our reporters to effectively use it. It took 24 hours from the launch of the application to the moment the first reporting feature was added—mainly because we spent much of the intervening time figuring out the scaling issues.

This time we handled this a lot better. We provided private pages exposing all recent activity on the site. We also provided public pages for each of the tags, as well as combination pages for party + tag, MP + tag, document + tag, assignment + tag and user + tag. Most of these pages were ordered by most-tagged, with the hope that the most interesting pages would quickly bubble to the top.

This worked pretty well, but we made one key mistake. The way we were ordering pages meant that it was almost impossible to paginate through them and be sure that you had seen everything under a specific tag. If you’re trying to keep track of everything going on in the site, reliable pagination is essential. The only way to get reliable pagination on a fast moving site is to order by the date something was first added to a set in ascending order. That way you can work through all of the pages, wait a bit, hit “refresh” and be able to continue paginating where you left off. Any other order results in the content of each page changing as new content comes in.

We eventually added an undocumented /in-order/ URL prefix to address this issue. Next time I’ll pay a lot more attention to getting the pagination options right from the start.

Rewarding our contributors

The reviewing experience the first time round was actually quite lonely. We deliberately avoided showing people how others had marked each page because we didn’t want to bias the results. Unfortunately this meant the site felt like a bit of a ghost town, even when hundreds of other people were actively reviewing things at the same time.

For the new version, we tried to provide a much better feeling of activity around the site. We added “top reviewer” tables to every assignment, MP and political party as well as a “most active reviewers in the past 48 hours” table on the homepage (this feature was added to the first project several days too late). User profile pages got a lot more attention, with more of a feel that users were collecting their favourite pages in to tag buckets within their profile.

Most importantly, we added a concept of discoveries—editorially highlighted pages that were shown on the homepage and credited to the user that had first highlighted them. These discoveries also added valuable editorial interest to the site, showing up on the homepage and also the index pages for political parties and individual MPs.

Light-weight registration

For both projects, we implemented an extremely light-weight form of registration. Users can start reviewing pages without going through any signup mechanism, and instead are assigned a cookie and an anon-454 style username the first time they review a document. They are then encouraged to assign themselves a proper username and password so they can log in later and take credit for their discoveries.

It’s difficult to tell how effective this approach really is. I have a strong hunch that it dramatically increases the number of people who review at least one document, but without a formal A/B test it’s hard to tell how true that is. The UI for this process in the first project was quite confusing—we gave it a solid makeover the second time round, which seems to have resulted in a higher number of conversions.

Overall lessons

News-based crowdsourcing projects of this nature are both challenging and an enormous amount of fun. For the best chances of success, be sure to ask the right question, ensure user contributions are rewarded, expose as much data as possible and make the “next thing to review” behaviour rock solid. I’m looking forward to the next opportunity to apply these lessons, although at this point I really hope it involves something other than MPs’ expenses.

More recent articles

- Weeknotes: Llama 3, AI for Data Journalism, llm-evals and datasette-secrets - 23rd April 2024

- Options for accessing Llama 3 from the terminal using LLM - 22nd April 2024

- AI for Data Journalism: demonstrating what we can do with this stuff right now - 17th April 2024

- Three major LLM releases in 24 hours (plus weeknotes) - 10th April 2024

- Building files-to-prompt entirely using Claude 3 Opus - 8th April 2024

- Running OCR against PDFs and images directly in your browser - 30th March 2024

- llm cmd undo last git commit - a new plugin for LLM - 26th March 2024

- Building and testing C extensions for SQLite with ChatGPT Code Interpreter - 23rd March 2024

- Claude and ChatGPT for ad-hoc sidequests - 22nd March 2024

- Weeknotes: the aftermath of NICAR - 16th March 2024